Sean Silver explains how Prussian blue works:

"The iron in Prussian Blue is in two different oxidation states – which is to say, has two different numbers of electrons. As iron(II), it has given up two electrons, and is a dark brown color. Iron(III) [where it's given up 3 electrons] is rust-red, precisely because rust is mostly composed of iron in that third oxidation state.

The ability of iron easily to switch between oxidation states happens to be what makes it crucial to blood – and makes blood visibly different when oxygenated. When the iron(II) in hemoglobin forms a bond with oxygen, it gives up an electron to become iron(III); it changes its oxidation state, and becomes bright red. That same compound will later give up its oxygen to a cell which needs it, reclaiming its electron and reverting to duller, darker color gained from iron(II).

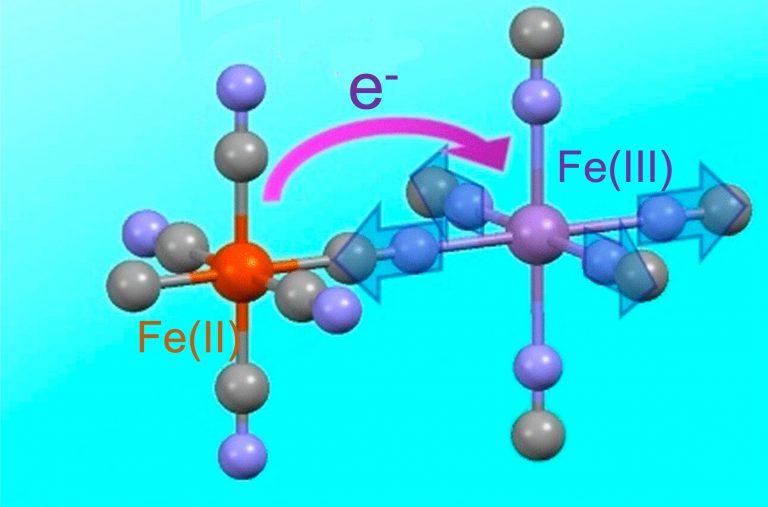

The blueness only happens when both ions are locked in close proximity, from a special process called intervalence charge transfer. When hit with light of the right wavelength, some of the iron(II) ions throw off an electron, which is captured by a neighboring iron(III). Though the individual atoms stay locked in the lattice, the ions switch places, one shedding an electron, which the other gains. Because the compound absorbs only the precise orange wavelength that triggers the charge transfer, it reflects everything else. In white light, our eyes register the sum of the reflection as blue."

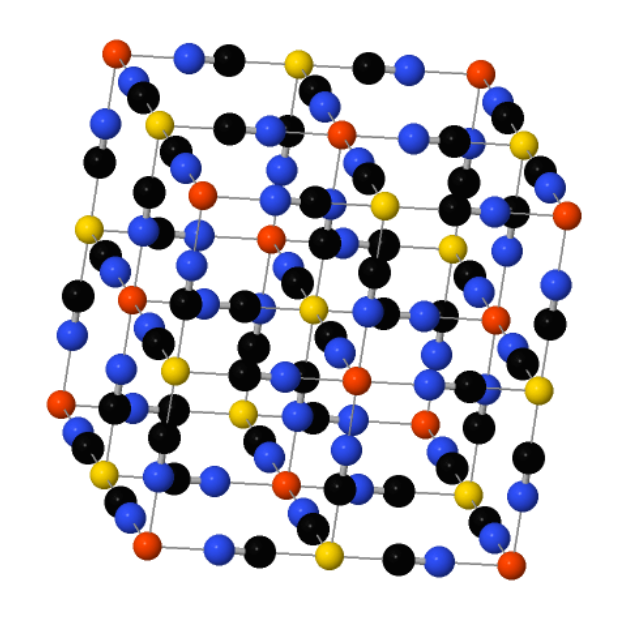

The picture shows how it works. But I don't quite get it: some irons touch 6 carbons and others touch 6 nitrogens. Is that why some are iron(II) and some are iron(III)? If no atoms move in this "intervalence charge transfer", that can't be right.

(2/n)